[By Tom Nicholls]

In the summer of 1974, Richard Nixon was under immense pressure and suffering from excessive alcoholism. During a meeting with two congressional members in the White House, he argued that impeaching the president for a “minor theft” at the Democratic National Committee headquarters would be absurd. According to Charles Ross, a North Carolina congressman, Nixon said: “I walked into the office, picked up the phone, and within 25 minutes, millions would have died.”

The 37th President likely intended to express the tremendous responsibility of the presidency, rather than making a direct threat, but he had already integrated his bizarre theory—his “crazy man theory”—into American foreign policy. Nixon ordered the deployment of nuclear-armed B-52 bombers in the Arctic to deter the Soviet Union. He urged National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger to “get something big,” considering establishing nuclear strike targets in Vietnam. As the presidency disintegrated, Nixon became consumed by anger and paranoia. However, until the moment he resigned, the “command and control” of the nuclear arsenal—a complex and precise system that allowed the president to launch weapons capable of destroying cities and killing hundreds of millions of people—was still in the hands of this restless individual, just as it had been for his four predecessors after World War II, forever in the hands of his successors.

For eighty years, the president of the United States has held the sole authority to order the use of U.S. nuclear weapons. If the commander-in-chief wanted to initiate an unexpected, baseless attack, escalate conventional conflicts, or retaliate with a full-scale nuclear war against a single nuclear aggression, then he had complete discretion. This command could not be revoked by anyone in the U.S. government or military. His power was absolute, making nuclear weapons in the defense sector for decades known as “the president’s weapon.”

Almost every U.S. president has experienced moments of emotional instability and impaired judgment, no matter how brief those moments were.

Dwight Eisenhower was hospitalized due to a heart attack, sparking nationwide debates about his suitability for public office and re-election. John F. Kennedy secretly took powerful medications for Addison’s disease, characterized by extreme fatigue and emotional instability. Ronald Reagan and Joe Biden battled the weaknesses of old age in their later years. At this moment, a small plastic card with a top-secret code—the private key to unlock America’s nuclear arsenal—is tucked into Donald Trump’s pocket. He is focused on demonstrating his leadership, rageful against enemies (real or imagined), and letting misinformation dictate decisions—while at the same time, local wars are poised to break out across the globe.

Nearly 30 years after the end of the Cold War, concerns over nuclear war seem to have subsided. Subsequently, relations between the United States and Russia were frozen, and Trump entered politics. Voters handed him the nuclear codes—twice, not once—despite his claims of launching “fire and fury” against another nuclear-armed state. Reports indicate that he questioned a senior advisor about why the US should possess nuclear weapons if it cannot use them. Now, he advocates for nearly doubling the US nuclear arsenal.

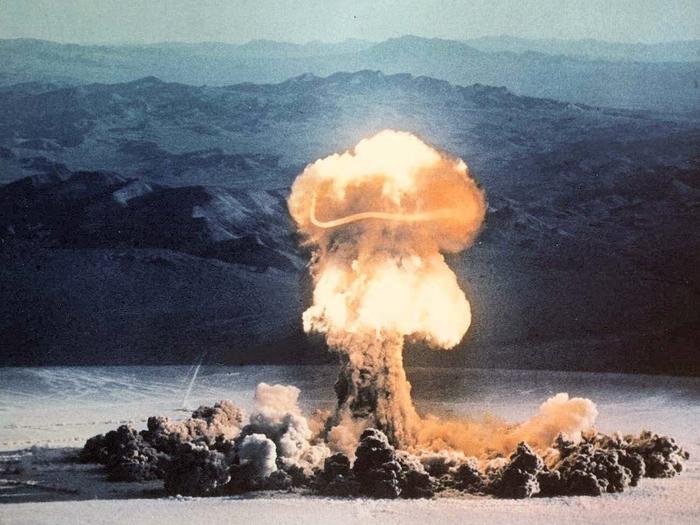

In 1957, the U.S. military conducted a series of nuclear tests in Nevada called “Operation Plumbbob.”

Russia has repeatedly threatened to use nuclear weapons in its conflict with Ukraine, which borders four NATO allies. India and Pakistan are both nuclear powers. In May this year, violent clashes erupted again in the Kashmir region between the two countries. North Korea plans to improve and expand its nuclear capabilities, posing a threat to American cities and further inflaming South Korea. Some leaders in South Korea are discussing whether they should develop their own nuclear weapons.

In June of this year, following Israel’s declaration of its determination to permanently eliminate the potential nuclear threat posed by Iran to its survival, an attack was launched against Iran by Israel and the United States.

The option for nuclear strikes in any conflict depends on the command and control system, which in turn relies on the authority of the president—and humanity. This system has been in place since World War II. Is it still effective today?

Perhaps the apocalypse begins with such an event. Whether the president orders preemptive strikes against enemies or responds to attacks against the United States or its allies, the process is the same: he first consults with senior civilian and military advisors. If he decides to use nuclear weapons, the president retrieves a leather-wrapped aluminum box, named “Football,” weighing about 45 pounds. It is carried by an officer assistant, who follows him wherever the commander goes; in many photos of the president’s travels, you can see the assistant holding this briefcase in the background.

This box contains no nuclear “buttons” for the president to personally launch weapons. It serves as a communication device, designed to quickly and reliably connect the commander to the Pentagon. It also includes options for targeting, listed on layered plastic sheets (according to those who have seen them, these sheets resemble the menu at Danny’s restaurant). These options roughly correspond to the scale of the strike. The target groups are classified, but nuclear experts have long joked that they could be categorized into three levels: “medium rare,” “medium well done,” and “well done.”

Once the president makes his choice, “Football” connects him to an official at the Pentagon, who immediately uses military voice codes to challenge the president, such as “Tango Delta.” To verify the command, the president must read the corresponding code from a plastic card tucked into his pocket (nicknamed “biscuits”).

He does not need to obtain other permissions; however, another official in the room, possibly the Defense Secretary, must confirm that the person using the code is indeed the President.

The Pentagon command center will then issue specific mission orders to the nuclear forces of the Air Force and Navy within two minutes. Whether it’s at a launch site deep beneath the Great Plains of North America, an aircrew compartment on a bomber runway in North Dakota or South Louisiana, or a submarine lurking in the depths of the Atlantic and Pacific, all personnel will receive target groups, codes, and orders to use nuclear weapons.

If enemy missiles attack, this process can be compressed into just a few minutes or even seconds. Nuclear weapons launched from Russian submarines in the Atlantic can strike the White House in just seven to eight minutes after being detected. The process of confirming the launch may take five to seven minutes, during which officials also have to eliminate technical errors.

Both the United States and Russia have made mistakes multiple times. According to Edward Lussac’s newly published biography of Brent Scowcroft, Jimmy Carter’s National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski received a phone call from his military aide late one night in June 1980. The aide told Brzezinski that hundreds—no, thousands—of Soviet missiles were approaching, and he should prepare to wake up the President. While waiting for military confirmation of the attack, Brzezinski decided not to wake his wife because he thought it would be better for her to die in her sleep than to know about what was about to happen.

The assistant reported that it was a false alarm. Someone accidentally entered training simulation information into the computer of the North American Aerospace Command.

In real attacks, there is hardly time for reflection. Only time can give the President confidence in the system and make decisive decisions about the fate of the world.

The destruction of Hiroshima changed the nature of war. Wars might still use conventional bombs and artillery, but now, nuclear weapons could instantly destroy entire countries.

Leaders from around the world, by intuition, realized that nuclear weapons were not just another tool at the hands of military commanders. As British Prime Minister Winston Churchill said to U.S. Secretary of War Henry Stimson in 1945, “What is dynamite? Insignificant. What is electricity? Meaningless. This atomic bomb is a second coming of anger.”

Harry Truman agreed with this sentiment. He never doubted the necessity of using atomic bombs on Japan, but he quickly took action to seize control of these weapons from the military. The day after the Hiroshima atomic bomb exploded, Truman declared that no other nuclear weapon could be used without his direct command—a stark contrast to his previous policy of “non-interference” regarding the issue of atomic energy. When the third atomic bomb was ready to be launched towards Japan, Truman established personal full control over the nuclear arsenal. Secretary of Commerce Henry Wallace wrote in his diary on August 10, 1945, that Truman did not like the idea of killing “all those children,” and added that the president thought it “too terrible to kill another 100,000 people,” making it unworthy of consideration.

On September 2, 1945, the former Japanese Imperial Foreign Minister Shigeru Kondo signed the surrender agreement on the US Navy’s “Missouri” battleship.

In 1946, Truman signed the Atomic Energy Act, firmly placing the development and manufacturing of nuclear weapons under civilian control. Two years later, a highly classified National Security Council document explicitly identified who was in charge: “The decision to use atomic weapons during wartime should be made by the President.”

The urgency for the U.S. military to use nuclear weapons was not baseless. In 1949, when the Soviet Union tested its first atomic bomb, some military officials urged Truman to take the initiative to destroy the Soviet nuclear program. “Damn it, we are at war!

“General Ovell Anderson said, “As long as I give the order, within a week, we can destroy five Soviet nuclear missile bases! After I meet with God, I think I can explain to him why I want to act now—now is too late—to do so. I could explain that I have saved civilization!”

The United States Air Force quickly relieved Anderson of his duties, but this general was not alone. High-ranking officials in American politics, the academic community, and the military all supported preemptive nuclear strikes against the Soviet Union. However, only the president’s opinion held sway.

Dwight D. Eisenhower came to power with the goal of limiting the use of nuclear weapons. However, as the command and control system evolved (to accommodate more advanced weapons and the growing threat from the Soviet Union), the president needed to be able to order varying degrees of nuclear strikes on various targets. Moreover, before he ordered any nuclear strike, he did not even need to formally inform Congress (let alone wait for Congress to declare war). If he wished, the president could actually go ahead and declare war on foreign countries with his own weapons.

In the early 1950s, the United States developed an original nuclear strategy aimed at containing the Soviet Union. The United States and its allies could not appear everywhere simultaneously, but they could make the Kremlin pay ultimate consequences for almost any type of destruction worldwide, not just nuclear attacks on the United States. This idea was known as the “massive retaliation” strategy: as John Foster Dulles, the Secretary of State during Eisenhower’s era, put it, it meant that the United States would commit to “an immediate retaliatory capability through our chosen means and locations.”

In October 1957, when the Soviet Union launched its first artificial satellite, Eisenhower’s approval ratings had been declining for several months. Despite his deep skepticism about the effectiveness of nuclear weapons, he still approved extensive military expansion, allowing for the launch of more targets.

“You can’t fight this kind of war,” he said at a White House meeting a month after the Soviet Union launched its satellite. “There simply isn’t enough bulldozers to clear the streets of bodies.”

Eisenhower’s successor harbored doubts about nuclear options, even though the U.S. military depended on it. Moreover, the system became increasingly difficult to manage: with the power of nuclear arsenals increasing, there was an increased likelihood of misunderstandings and miscalculations.

In 1959, the missile era replaced the bomber era, making nuclear decision-making more complex. Intercontinental ballistic missiles orbiting the world at several times the speed of sound were more terrifying than Soviet bombers hovering over the Arctic. Suddenly, the president’s window for major decisions shrunk from hours to minutes, making broader deliberation impossible and highlighting the necessity of having one person in charge of nuclear decisions.

Around the same time, the Soviet Union surrounded the U.S., French, and British troops stationed in Berlin, creating direct confrontations between the East and West—increasing the possibility of a nuclear war and exacerbating the president’s pressure. If Western countries refused to retreat from any local conflicts elsewhere in the world, the Soviets might invade West Germany, betting that doing so would lead to the collapse of NATO and force Washington to capitulate. Meanwhile, Americans bet that using (or threatening to use) nuclear weapons would deter (or deter) such an invasion.

But if either side crossed the nuclear threshold on the European battlefield, the game quickly boiled down to: Which superpower would be the first to launch a full-scale attack on the enemy’s homeland?

Under this policy of nuclear near-war, every decision by the president could trigger disaster. Staying in Washington meant facing the risk of being killed; if he left the White House, the Soviets might see it as a signal from the Americans preparing to strike—which in turn would provoke Soviet fears, prompting them to decide on preemptive nuclear strikes.

In this frenzy, the lives and future of millions of people around the world hinge on the perceptions and emotions of the President of the United States and his adversaries in the Kremlin.

The President makes decisions, but the staff are responsible for planning, and their job is to find targets for bombing. By the end of 1960, before Kennedy took over the White House, the U.S. military had developed its first set of plans to coordinate all nuclear forces in the event of a nuclear war. It was called “Total Nuclear War Single Integrated Operation Plan” (SIOP), but it wasn’t much of a plan at all.

During the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, U.S. President Kennedy conversed with senior U.S. military officers such as Curtis LeMay (second from right).

The “Total Nuclear War Single Integrated Operation Plan” (SIOP) of 1961 envisaged not only directing American nuclear weapons against the Soviet Union but also China, even if China did not engage in a war with the United States. More than just an option, it was a command that would kill at least 400 million people regardless of how the war started. Kennedy’s military advisors straightforwardly (and correctly) told him that after being hit by such a scale of attacks, there would definitely be some weapons left in the Soviet nuclear arsenal that would survive—and cause terrible damage to North America. This soon became known as “mutual assured destruction.” According to John Rupert, a defense department official, during a SIOP briefing chaired by General Thomas Powers, a rational voice rose up, “If this isn’t a war against China?” That voice asked. “If it’s just a war against the Soviet Union? Can you change the plan?”

“Well, yes,” General Powers said helplessly, “We can, but I hope no one will think of this because it would completely ruin the whole plan.” “I only hope you don’t have relatives in Albania,” Powers added, because the plan also included bombing a Soviet facility in the small country.

David Sumner, the Commander of the United States Marine Corps, was one of those who despised the plan, stating that it “didn’t reflect American ways.” Luber later wrote that feeling was like witnessing Nazi officials orchestrating a mass extermination scheme.

Since Eisenhower, every president has been shocked by the nuclear options they hold. Even Nixon was astonished by the scale of casualties projected in the latest Situational Operation Plan (SIOP). In 1974, he ordered the Pentagon to develop a “limited” nuclear warfare strategy. When Henry Kissinger requested a plan to prevent Soviet invasion of Iran, the military suggested dropping nearly 200 nuclear bombs at the Iranian-Soviet border. “Are you crazy?” Kissinger exclaimed during a meeting. “Is this a limited option?”

By the end of 1983, Ronald Reagan had heard briefings on the latest SIOP plan and wrote in his memoirs: “Some people in the Pentagon still claim that nuclear war can be won. I think they are insane.” Before his death, Reagan’s advisor Paul Nitze told an ambassador: “You know, I advised Reagan never to use nuclear weapons. In fact, I told him that even nuclear weapons should not be used, especially in retaliatory strikes.”

At the end of the Cold War, despite the system still being commanded by the president, it had developed into an almost uncontrollable situation: a highly technological disaster generator aimed at transforming inconceivable options into devastating actions. Each president was restricted: essentially, there was only one command center with virtually no control over operations. In 1991, George H.W. Bush began to reduce this overly large system, leading to significant cuts in both the number of U.S. nuclear weapons and targets. However, with presidential changes, war planners remained: in the years following Bush’s departure, the U.S. military increased the list of targets by 20%.

Since the end of the Cold War, the United States has undergone some meaningful reforms, including negotiations on significantly reducing nuclear stockpiles between the United States and Russia, as well as the development of additional safeguards against technological failures. For instance, in the 1990s, American ballistic missiles were aimed at international waters to prevent accidental launches. However, should a nuclear crisis erupt, the president would still face plans and options not designed by him, or even those he desired.

In 2003, the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI) was replaced by the “Strategic Deterrence and Military Equipment Deployment Plan” (OPLAN). This plan seemingly granted the president more options beyond the destruction of all humanity, including the option to delay countermeasures rather than immediately retaliate. However, reports indicate that the initial OPLAN also included options to destroy small non-nuclear states. Despite the secrecy surrounding details, military exercises and non-confidential documents over the past two decades suggest that this modern nuclear plan largely mirrors its predecessor from the last century.

The concentration of presidential power, the compression of decision-making time, and the systematic targeting of military planners have all contributed over more than eighty years to creating an institution burdened with significant and unnecessary risks—and the president still retains the right to order nuclear strikes under any reason deemed appropriate. However, there are ways to reduce this risk without compromising the basic strategy of nuclear deterrence.

To limit the president’s reckless actions and lower the likelihood of a world-ending scenario, the first thing the United States can do is commit to the policy of “no first use” of nuclear weapons. Earlier this year, a bill prohibiting preemptive nuclear strikes without congressional approval was reintroduced in the House of Representatives, although it is unlikely to pass. If Congress does not approve, any president could pledge not to use nuclear weapons first through executive orders, which might create breathing space during crises (provided the adversary trusts the president).

Every president should insist that in the face of impending threats, options available include more limited retaliatory strikes and smaller-scale comprehensive responses. In other words: remove items from the “Dennis Restaurant Menu” we do not need, and reduce the existing portions. The United States might only need to deploy a few hundred strategic nuclear warheads—not currently around 1500—to maintain deterrence. Even with such a minimal deployment, no country has enough firepower to completely destroy all U.S. secondary nuclear retaliation capabilities through preemptive strikes. If a president orders a reduction in the number of deployed warheads while still maintaining a threat to key targets, it could regain partial control over nuclear systems, much like Congress can limit presidential nuclear options through legislation. This would make the world safer.

Of course, none of these measures can solve the fundamental problem of the nuclear dilemma: human survival depends on an imperfect system that functions perfectly. Command and control systems rely on technology that must always be operational and minds that must remain calm at all times. Some defense analysts doubt whether artificial intelligence—which reacts faster and more calmly than humans to information—can alleviate some of the burden on nuclear decision-making. This is a very dangerous idea. Artificial intelligence may help quickly organize data and distinguish real attacks from misjudgments, but it is not foolproof. Presidents do not need algorithms for instant decisions.

The officer responsible for safeguarding the “nuclear briefcase” by the president.

In terms of preventing large-scale attacks, empowering the president with sole authority seems to be the best choice. Under urgent circumstances, groupthink can be as dangerous as individual madness; retaliatory orders must be decided by the president—above any bureaucratic institution and distinct from military exercises.

However, the decision to initiate preemptive nuclear strikes should be a political debate. The President should not have the sole right to initiate nuclear warfare.

But what happens if a president with poor judgment and morals takes office or if the President’s conduct is corrupt during his term? What is the only entity that can directly constrain a rash President is the chain of command personnel who must choose to relinquish their duties in order to delay or obstruct commands they deem reprehensible or insane. However, military personnel are trained to obey and execute orders; a coup d’etat is not foolproof. The President can dismiss or replace anyone who impedes this process. American military personnel should never be granted the power to prevent commands that contravene reason; manipulating this situation will undermine national security and democracy itself.

When I asked a former Air Force missile squadron commander about whether senior officers could refuse orders to launch nuclear weapons, he said, “We were told we could refuse illegal and immoral orders.” He paused. “But no one ever explained what ‘immoral’ meant.”

Ultimately, American voters themselves provide a form of security. They decide who will control the top levels of command and control systems. When they go to vote, they naturally consider healthcare, egg prices, and how much it costs to fill up a tank. But they must also remember that they are essentially placing nuclear codes in the hands of someone. Voters must elect a president capable of clear thinking in crisis and broad strategic planning. They must select leaders with good judgment and strong character.

As the sole steward of America’s nuclear arsenal, the President’s most important duty is to prevent nuclear war. And voters’ most important duty is to elect the right person to bear this responsibility.

(Originally published on the Atlantic Monthly’s commentary website, with the original title: “The President’s Weapon: Why Does the Power to Launch Nuclear Weapons Lie in the Hands of an American?” The translation is from the “Dynasty Newspaper” WeChat public account, does not represent the views of Guanchao.com.)