Cailian Press, July 25th (Editor: Xiaoxiang)

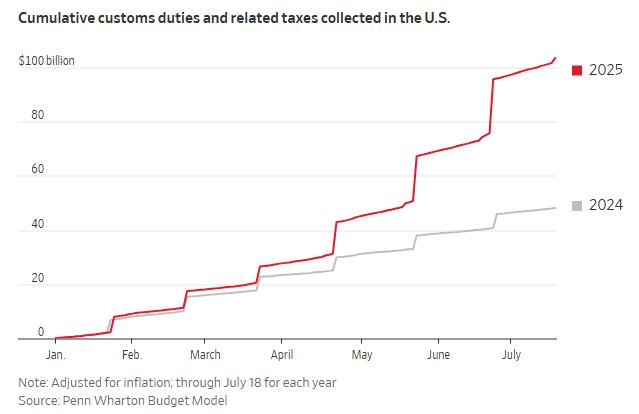

The U.S. government has so far imposed an additional $55 billion in tariffs this year, and from the current situation, American businesses have largely shouldered this expense…

President Trump’s ongoing imposition of tariffs over the past few months has pushed the level of U.S. tariff rates to a peak not seen in decades. These tariffs are typically paid by importers upon the arrival of goods at U.S. ports. Therefore, it is not difficult to guess who will ultimately pay these costs to customs—usually manufacturers, logistics companies, or brokerage firms, or in some cases, the retailers who order the goods themselves.

However, economists and other industry insiders have been focusing on who will ultimately bear the cost: foreign suppliers—by reducing their front-end prices; U.S. consumers—by paying higher prices at checkout; or the American businesses in between—taking the bulk of the burden?

Currently, increasingly clear signs point to American businesses absorbing most of the tariff costs—from General Motors, Nike to local flower shops.

This is mainly because in competitive markets, companies that raise prices may hand over market share to competitors who maintain price stability. Many companies are reluctant to raise prices unless forced.

However, for these enterprises, even though they temporarily swallow the “big chunk” of tariffs, it does not mean they can do so forever—many have indicated plans to increase prices in the coming months, which clearly will shift these costs onto U.S. consumers.

Currently, U.S. President Donald Trump is set to finalize his countervailing tariff rates on major trading partners in the coming week, undoubtedly bringing some urgent policy certainty to American businesses. However, this could also lead to a broader price increase for thousands of imported goods…

American Businesses “Bite the Big One”

According to estimates by industry organizations, although there are signs that some foreign suppliers have lowered prices for some commodities to help alleviate pressure on American buyers, this support is far from reaching the level Trump promised—that foreign countries would bear the tariff costs.

In economic indicators, the Import Price Index (IPI) is typically used to track the prices paid by importers before paying import duties. This index has remained stable in recent months. Some economists say this indicates that foreign suppliers have not generally reduced prices to offset their American customers’ costs.

Goldman Sachs conducted what it calls a more refined analysis of import prices, concluding that foreign companies seem to have absorbed about 20% of the tariff costs through price reductions.

So far, the overall inflation rate for U.S. consumers remains moderate. Although the CPI rose to 2.7% year-over-year in June, the core inflation rate was below expectations because many companies reduced purchases or hoarded inventory before the tariffs took effect. However, there are signs that the inflation rate for some of the most affected goods—including furniture, toys, and clothing—has indeed begun to gradually climb.

Preston Caldwell, Chief U.S. Economist at Morningstar, stated, “American businesses are still bearing most of the tariff costs and have not passed most of these costs onto consumers.”

A typical consequence of American businesses “bearing the burden of tariffs” is that there are already signs of profit losses in the second quarter performance reports.

General Motors announced this week that it paid more than $1 billion in import duties for its vehicles in the second quarter. Mary Barra, CEO of General Motors, stated that the company has not yet significantly raised prices due to the tariffs but did not rule out the possibility of price hikes. Stellantis, a French-based automaker that owns American brands like Ram and Jeep, also reported this week that the import duties have resulted in a loss of $350 million in profits.

Additionally, the aerospace and defense company RTX mentioned that the tariff cuts into its profits. Toy manufacturer Hasbro, on Wednesday, indicated that although the financial impact of the tariffs on the most recent quarter was below expectations, some effects may still emerge. The company stated that the tariffs could result in an additional expense of $60 million throughout the fiscal year.

Last month, Nike executives also predicted that the tariffs would lead to a reduction in the company’s profits by about $1 billion for the fiscal year.

Economists estimate that the actual average tariff rate on all imported goods in the United States is now close to 17%, far higher than last year’s 2.3%.

Is it time for American consumers?

Many large companies had previously been reluctant to directly link price increases with tariffs to avoid angering Trump.

Following Walmart’s announcement in May that certain items would increase in price for a few days, Trump had previously posted online that Walmart should “eat the tariffs” (eat the tariffs) rather than raise prices.

However, once more tariffs are raised in August, and the stockpile of goods previously accumulated is depleted, even if Trump were angry, it seems inevitable that American retailers will have to raise prices.

This also means that American consumers might soon face broader impacts.

In May this year, Walmart announced that it had begun to raise prices for some items to offset the cost of tariffs and said there would be more price increases this summer.

For example, in May, tariffs on goods from South America and Central America increased the retail price of bananas, one of the most frequently purchased items by consumers at Walmart, from 50 cents per pound to 54 cents.

Shayai Lucero, a flower shop owner near Albuquerque, New Mexico, is dealing with some of the additional tariff costs but has also raised prices. She buys long-stemmed roses imported from South America from wholesalers in the United States, which used to cost between $1.15 and $1.35 per stem. Now, they have risen to $1.95 to $2.15. This has forced her to raise the bottled price of a bouquet of 12 roses from $60 to $69.

Matt Priest, CEO of the American Footwear Distributors and Retailers Association, mentioned that some footwear companies have announced plans to increase prices in the coming weeks.

“So far, brand and retailer have absorbed most of the impact, but they can only hold out for a while,” Priest said when discussing his member companies.

Approximately 99% of shoes sold in the United States are imported from China, Vietnam, Italy, and other countries.