Since the beginning of this year, institutions such as the International Monetary Fund, World Bank, and World Trade Organization have all lowered their forecasts, pointing out that a fundamental change is underway:

Trade tensions continue to escalate, uncertainty reaches a historical high, and the economic outlook is dominated by the ongoing downward risks.

Recent data shows that, based on current developments, the global average growth rate for the first seven years of the 2020s could become the slowest in any decade since the 1960s.

Through data analysis, Tan Zhi has captured that behind the fluctuations in confidence are a series of key issues emerging:

Who is most affected by the current international trade conflict?

Will high tariff policies lead to a transformation of the global trade model and a reorganization of the international trade landscape?

How will global trade growth be maintained in the future?

Facing these grand and complex questions, data can offer some insights.

How should we evaluate the impact of US tariffs?

In recent times, many reports and analyses have discussed the impact of US tariffs.

As the world’s second-largest trading nation and the largest trading partner of many major economies, changes in US trade policy have naturally raised concerns among nations.

However, Tan Zhi wants to share a set of data.

The bilateral trade volume between the United States and many countries ranks at the forefront of the world, such as:

US-China, US-Mexico, US-Canada, US-Germany.

Under this round of tariff impact, in April, China, Mexico, Canada, and Germany’s exports to the US decreased by 13.6%, 12.7%, 17.5%, and 15.9% respectively compared to the previous month.

These fluctuations seem dramatic, but their impact on the total volume of global trade is relatively limited.

Statistical data shows that in April, the global trade volume only decreased by 1.4% month-on-month.

Adding up, in April, the US imports plummeted by nearly 20.0% month-on-month.

Based on the previous calculation, which assumed that the United States accounted for 13% of global imports, theoretically, it should have dragged down global trade by about 2.6%, nearly twice the actual decline.

This discrepancy is significant for international trade.

It breaks a long-standing pattern:

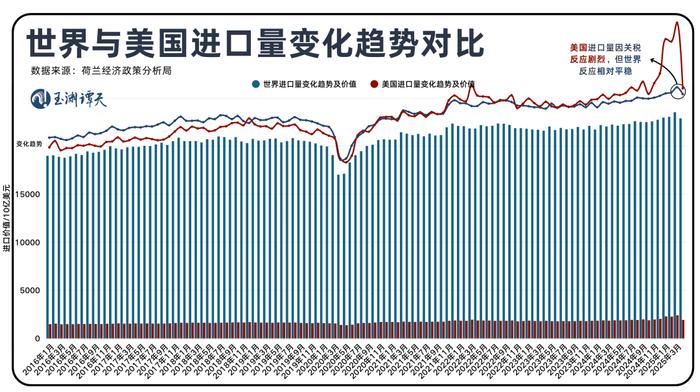

The high correlation between global and US trade fluctuations.

Using import data as an indicator, over the past decade, the trends in global trade have largely aligned with those in US trade.

However, recently, these two curves, which were originally overlapping, have begun to diverge:

Since the end of last year, the volume of imports in the United States has fluctuated greatly, while global imports have changed relatively smoothly.

This phenomenon indicates that the impact of US policies on global trade is not as significant. The global trade system is gradually reducing its reliance on the United States, demonstrating greater independence and resilience.

Long-term data also presents the same conclusion.

In recent years, the volume of global goods trade has essentially maintained growth. The only notable decrease occurred in 2020, mainly due to the pandemic.

From 2017 to 2021, Trump’s presidency saw a shift towards trade protectionism. However, global goods trade still maintained growth.

From 2021 to 2025, Biden continued some of Trump’s policies and strengthened trade restrictions in areas such as technology. Even so, global trade recovered after the pandemic.

This indicates that, at certain levels, the international trade system has gradually adapted and surpassed the influence of US policies.

With this round of tariff shocks, the direction of international trade further intersects with that of US trade, making such trends more pronounced.

How does ‘survival and development’ new growth emerge?

So, where does this force that transcends US policy come from?

We can analyze it from two aspects: internal adjustments within bilateral relations directly related to the United States, and structural changes in the global trade system.

Over the past period, many countries have sought to substitute trade in order to mitigate the short-term impact of U.S. tariffs.

However, such strategies come at a cost: “downward competition” for developing countries, which must lower labor and resource prices to maintain cost advantages.

In the long run, this can lead developing countries into a cycle of low economic levels, making it difficult for international trade to continue growing.

The limitations of trade substitution reflect the structural issues within international trade—the disadvantageous position of developing countries.

Data shows that even under most-favored-nation treatment, developing country agricultural exports face an average import tariff of nearly 20%, textiles and apparel face an average import tariff of 6%, significantly higher than the average level in developed countries. These high tariffs already limit the competitiveness of developing countries.

Without the tariffs imposed by the United States, other tariffs and non-tariff barriers (such as technical standards) may still exist, continuously weakening the market position of developing countries.

Trade substitution can alleviate the impact of tariffs in the short term but cannot fundamentally solve such structural problems.

New growth points need to be found in new trade structures.

International trade conflicts present an opportunity, often accompanied by changes in global production models and modes of economic growth.

Currently, 87% of global trade occurs outside the United States. In 2024, the growth rates of trade in Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East all exceeded the global average.

These regions are reshaping their production models through technological innovation and strategic investments.

Among them, the Middle East is particularly worth mentioning.

The Middle East is a typical example of overcoming its original position in the international trade landscape to find new growth points.

Traditionally, the status of Middle Eastern countries in international trade was mainly dependent on oil exports. In recent years, Middle Eastern countries have been accelerating their layout in emerging industries such as artificial intelligence and clean energy.

Research data indicates that, based on current developments, by 2035, these investments are expected to contribute 20.9% to the growth of the GDP in the Middle East region.

It is noteworthy that these investments not only propel the economic development of the Middle East but also alter its strategic position in the international trade landscape.

In earlier years, we rarely regarded the Middle East as a separate trading area, instead habitually categorizing the world into three major trading blocs: Asia, Europe, and North America.

Today, the situation is entirely different.

New industries have helped transform the Middle East into a key node for global supply chain reorganization:

The UAE has become a transit center between Asia and Europe through the construction of the Jebel Ali Free Zone and the Port of Khalifa.

Saudi Arabia supports the global supply chain of technological products through the Ghawar and Yanbu port projects.

Kuwait has enhanced its competitiveness in the global supply chain by improving the business environment and introducing electronic customs clearance systems.

The rising status of the Middle East in global trade reflects the transfer of global economic power balances, which is very meaningful for developing countries to break through the structural constraints of international trade.

It is worth noting that the transformation of the Middle East was not recent; it was an active change based on long-term strategic planning.

If manufacturing development plans were used as indicators for assessing strategic planning capabilities, it would be found that these plans were already launched by Middle Eastern countries such as the UAE and Saudi Arabia well before the emergence of protectionist trade policies in 2016.

Today, strategic planning and adaptability are equally important.

Tan Zhi has reviewed the planning of the most trade-dependent developing countries, finding that most countries recognize this. China naturally does not need to elaborate further, but among other countries:

Asia-Pacific countries and Middle Eastern countries generally have their development plans in place relatively early. Latin American countries have caught up in recent years.

The backdrop of the times has changed, with protectionist trade policies emerging one after another, an undeniable reality.

In this context, countries need to balance adaptability with long-term planning to redefine their positions in the global economy. This ability to integrate adaptation with vision is a source of strength that transcends various obstacles and impacts.

What direction does ‘Diversification and Connection’ take in the global trade restructuring?

The new international trade pattern is gradually forming under the push of these forces.

We can start by examining the trade partnerships between the world’s major trading nations, observing the direction of global trade restructuring through changes in trade network connectivity.

Tan Zong has reviewed the changes in trade partnerships among China, Germany, the Netherlands, Japan, and South Korea, which are among the top five global trading nations.

Setting the comparative axis at this year versus 2016 (before the United States fell into trade protectionism):

In the chart above, countries whose rankings have significantly changed (a change greater than 3) are indicated with solid lines representing an increase and dashed lines representing a decrease, with different colors representing different regions.

Upon first glance, there are many countries with solid lines indicating growth, seeking new trade partners, while dashed lines show that the relative importance of traditional trade partners is declining. The international trade landscape is becoming more diverse.

“Diversity” has been a term we’ve heard about for many years. If I don’t buy your goods, I can still buy from others, it seems to be called “diversity.”

However, when choosing who to partner with, countries exhibit varying preferences, reflecting the differences in the concept of “diversity.”

This difference affects the resilience and expansion of trade networks.

Germany stands out in several charts because its changes are monochromatic, indicating that Germany’s main trade partners are mainly within Europe.

Tan Zong further analyzed the changes in U.S. trade partnerships and found similar characteristics:

The changes in U.S. trade partners are concentrated in allies in the Asia-Pacific region and Europe.

This indicates that the changes in these countries are essentially within their respective trade blocs, reflecting a prioritization of geopolitical alliances.

In recent years, the old trading powers of the US and Europe have justified “trade diversification” as an excuse, while Europe has actually clung to “European-centeredness,” and the United States has actually promoted strategies such as “nearshore outsourcing.”

Reality has shown that this approach often leads to increased uncertainty and contraction in the trade network.

For example, European restrictions on China’s technology exports have limited its competitiveness in the Asian market. The US’s “nearshore outsourcing” has, paradoxically, weakened its supply chain efficiency due to rising costs.

In contrast, China, Japan, and South Korea have chosen partners across more regions:

China is particularly prominent. On one hand, Asia-Pacific countries have gradually taken a dominant position among China’s trade partners. Among China’s top ten trading partners, more than half are from the Asia-Pacific region, including South Korea, Japan, Vietnam, Malaysia, Indonesia, and India.

On the other hand, in addition to deepening regional economic cooperation in the Asia-Pacific, China has also established closer connections with countries in Latin America and the Middle East. These regions have seen significant increases in their rankings among China’s trade partners.

Japan and South Korea have also strengthened their trade ties with regions such as Europe and the Middle East while deepening cooperation in the Asia-Pacific.

These practices represent another direction towards “diversification”:

Diversification is not just about changing trade partners but also about expanding the geographical breadth and depth of the trade network.

Compared to the regional concentration of the US and Europe, cross-regional diversification has a characteristic that related countries participate not only in the production process but also in high-value-added segments (such as R&D and setting of technical standards).

To distinguish between the two, there is a simple method: Are you creating value or are you dividing benefits?

Take China’s cooperation with the Latin American region as an example.

As shown in the chart, over the past decade, the trade status of China with the Latin American region has significantly improved.

In 2024, China’s trade volume with Latin America grew to more than double that of 2015.

Behind this data lies not only the effective diversification of market risks (which is evident in China’s pursuit of alternative imports for American agricultural products) but also China’s role in enhancing the economic added value of Latin American countries through participation in infrastructure development, technical cooperation, and industrial investment in these countries. This mutual enhancement of positions on the value chain has occurred.

By 2025, the global trade landscape is at a critical juncture. Although the unpredictability of US tariff policies has created uncertainty, it has also accelerated the global trade system towards a truly diverse direction.

Through data analysis, we can see that although the United States remains an important participant in global trade, its influence is gradually weakening. Developing countries and emerging economies, especially in Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East, are becoming new growth points in global trade.

Against this backdrop, globalization is not a passing trend but is reshaping the international trade landscape in new forms.

Diversified trade cooperation and the reconstruction of international relations indicate that the global trade system is adapting to new challenges and moving towards a more resilient and inclusive direction.