[By Tom Nicholls]

In the summer of 1974, Richard Nixon was under immense pressure and suffering from excessive alcoholism. During a meeting with two congressmen in the White House, he argued that impeaching the president for a “minor theft” at the Democratic National Committee headquarters would be absurd. According to Charles Ross, a North Carolina congressman, Nixon said: “I walked into the office, picked up the phone, and within 25 minutes, millions of people would die.”

The 37th President likely intended to express the tremendous responsibility of the presidency, rather than making a direct threat, but he had already incorporated his bizarre theory—his “madman theory”—into American foreign policy. Nixon ordered the deployment of nuclear-armed B-52 bombers in the Arctic to deter the Soviet Union. He urged Henry Kissinger, the National Security Advisor, to “do something big,” considering establishing nuclear strike targets in Vietnam. As the presidency began to crumble, Nixon became consumed by anger and paranoia. However, until the moment he resigned, the “command and control” of the nuclear arsenal—a complex and precise system that allowed the president to launch weapons capable of destroying cities and killing hundreds of millions of people—was still in the hands of this restless man, just as it had been for his four predecessors after World War II, who would also forever hold it in their successors’ hands.

For eighty years, the only power the president of the United States has over ordering the use of nuclear weapons is absolute. If the commander-in-chief wants to initiate an unexpected, baseless attack, escalate conventional conflicts, or retaliate with a full-scale nuclear war against a single nuclear aggression, then he has complete discretion. This order cannot be revoked by anyone in the U.S. government or military. His power is so absolute that for decades, nuclear weapons have been referred to as “the president’s weapon” in the defense sector.

Almost every U.S. president has experienced moments of emotional instability and impaired judgment, no matter how brief these periods may be.

Dewey Eisenhower was hospitalized due to a heart attack, sparking nationwide debates about his suitability for public office and re-election. John F. Kennedy secretly took powerful medications for Addison’s disease, characterized by extreme fatigue and emotional instability. Ronald Reagan and Joe Biden battled the weaknesses of old age in their later years. At this moment, a small plastic card with a top-secret code—the private key to unlock America’s nuclear arsenal—is tucked into Donald Trump’s pocket. He is focused on demonstrating his leadership, rageful against enemies (real or imagined), and letting misinformation guide his decisions—while at the same time, local wars are poised to break out across the globe.

Nearly 30 years after the end of the Cold War, concerns over nuclear war seem to have subsided. Subsequently, relations between the United States and Russia were frozen, and Trump entered politics. Voters handed him the nuclear codes—twice, not once—despite his claims of launching “fire and fury” against another nuclear-armed state. Reports indicate that he questioned a consultant about why the US should possess nuclear weapons if it cannot use them. Now, he advocates for nearly doubling America’s nuclear arsenal.

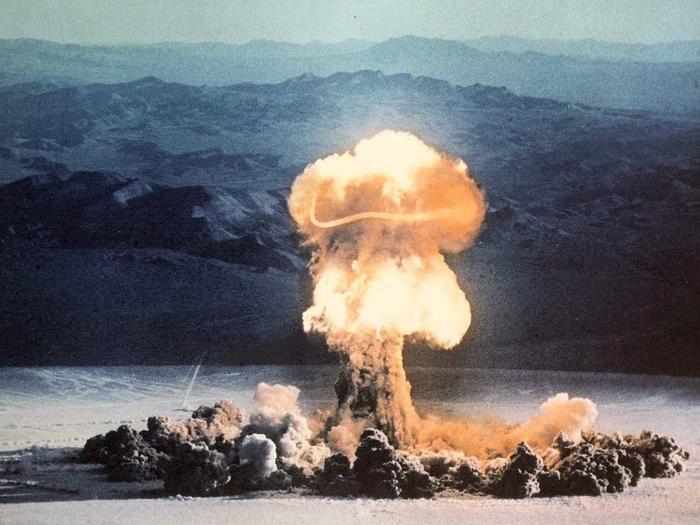

In 1957, the U.S. military conducted a series of nuclear tests in Nevada called “Operation Plumbbob.”

Russia has repeatedly threatened to use nuclear weapons in its war with Ukraine, which is bordered by four NATO allies. India and Pakistan are both nuclear powers. In May this year, violent clashes erupted again in the Kashmir region between the two countries. North Korea plans to improve and expand its nuclear capabilities, posing a threat to American cities and further inflaming South Korea. Some leaders in South Korea are discussing whether they should develop their own nuclear weapons.

In June of this year, following Israel’s announcement of its determination to permanently eliminate the potential nuclear threat posed by Iran to its survival, an attack was launched against Iran by Israel and the United States.

The option for nuclear strikes in any conflict depends on the command and control system, which in turn depends on the authority of the president—and humanity. This system has been in place since World War II. Is it still effective today?

Perhaps the end of the world is just beginning. Whether the president orders a preemptive strike against the enemy or responds to attacks against the United States or its allies, the process remains the same: he first consults with senior civilian and military advisors. If he decides to use nuclear weapons, the president retrieves a leather-wrapped aluminum box, known as “Football,” weighing about 45 pounds. It is carried by an officer assistant, who follows him wherever he goes; in many photos of the president’s travels, you can see the assistant holding this briefcase in the background.

This box contains no nuclear “buttons” for the president to personally launch weapons. It is a communication device designed to quickly and reliably connect the commander-in-chief with the Pentagon. It also includes options for targeting, listed on layered plastic sheets (according to those who have seen them, these sheets resemble the menu at Danny’s restaurant). These options are roughly categorized by the scale of the strike. The target groups are classified, but nuclear experts have long joked that they could be divided into three levels: “medium,” “medium-well,” and “well done.”

Once the president makes his choice, “Football” connects him to an official at the Pentagon, who immediately uses military voice codes to challenge the president, such as “Tango Delta.” To verify the command, the president must read the corresponding code from a plastic card in his pocket (nicknamed “biscuits”).

He does not need to obtain other permissions; however, another official in the room, possibly the Defense Secretary, must confirm that the person using the code is indeed the President.

The Pentagon command center will then issue specific mission orders to the nuclear forces of the Air Force and Navy within two minutes. Whether it’s at a launch site deep beneath the Great Plains of North America, an aircrew compartment on a bomber runway in North Dakota or South Louisiana, or a submarine lurking in the depths of the Atlantic and Pacific, all personnel will receive target groups, codes, and orders to use nuclear weapons.

If enemy missiles are launched, this process can be compressed into just a few minutes or even seconds. Nuclear weapons fired from a Russian submarine in the Atlantic can hit the White House in just seven to eight minutes after being detected. The process of confirming the launch may take five to seven minutes, during which officials also have to eliminate technical errors.

Both the United States and Russia have made mistakes multiple times. According to Edward Lussac’s newly published biography of Budge, Jimmy Carter’s National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski received a phone call from his military aide in the middle of the night in June 1980. The aide told Brzezinski that hundreds—no, thousands—of Soviet missiles were approaching, and he should prepare to wake up the President. While waiting for military confirmation of the attack, Brzezinski decided not to wake his wife because he thought it would be better for her to die in her sleep than to know about what was about to happen.

The assistant reported that it was a false alarm. Someone accidentally entered training simulation information into the computer of the North American Aerospace Command.

In real attacks, there is hardly time for reflection. Only time can give the President confidence in the system and make decisive decisions about the fate of the world.

The destruction of Hiroshima changed the nature of war. Wars might still use conventional bombs and artillery, but now, nuclear weapons could instantly destroy entire countries.

Leaders from around the world, acting on intuition, realized that nuclear weapons were not just another tool at the hands of military commanders. As British Prime Minister Winston Churchill said to U.S. Secretary of War Henry Stimson in 1945, “What is dynamite? Insignificant. What is electricity? Meaningless. This atomic bomb is a second coming of fury.”

Harry Truman agreed with this sentiment. He never doubted the necessity of using atomic bombs against Japan, but he quickly took action to seize control of these weapons from the military. The day after the Hiroshima atomic bomb exploded, Truman declared that no other nuclear weapon could be used without his direct command—a stark contrast to his previous policy of “non-interference” regarding the issue of atomic energy. When the third atomic bomb was ready to be launched towards Japan, Truman established personal full control over the nuclear arsenal. Secretary of Commerce Henry Wallace wrote in his diary on August 10, 1945, that Truman did not like the idea of killing “all those children,” and added that the president thought it was “too terrible” to kill another 100,000 people and deemed it unworthy of consideration.

On September 2, 1945, the former Japanese Imperial Foreign Minister Shigeru Kondo signed the surrender agreement on the USS Missouri battleship in the United States.

In 1946, Truman signed the Atomic Energy Act, firmly placing the development and manufacturing of nuclear weapons under civilian control. Two years later, a highly classified National Security Council document explicitly defined who was in charge: “The decision to use atomic weapons during wartime should be made by the President.”

The urgency for the U.S. military to use nuclear weapons was not baseless. In 1949, when the Soviet Union tested its first atomic bomb, some military officials urged Truman to strike first and destroy the Soviet nuclear program. “Damn it, we’re at war!

“General Ovell Anderson said, “As long as I give the order, within a week, I can destroy five of Soviet’s nuclear bomb bases! After I meet with God, I think I can explain to him why I want to act now—now, before it’s too late—to do so. I could explain that I have saved civilization!”

The United States Air Force quickly relieved Anderson of his duties, but this general was not alone. High-ranking officials in American politics, the academic community, and the military all supported preemptive nuclear strikes against the Soviet Union. However, only the President’s opinion held sway.

Dwight D. Eisenhower came to power with the goal of limiting the use of nuclear weapons. However, as the command and control system evolved (to accommodate more advanced weapons and the growing threat from the Soviet Union), the President needed to be able to order varying degrees of nuclear strikes on various targets. Moreover, he did not even need to formally inform Congress before ordering any nuclear strike (let alone wait for Congress to declare war). If he wished, the President could actually go ahead and declare war on foreign countries with his own weapons.

In the early 1950s, the United States developed an original nuclear strategy aimed at containing the Soviet Union. The United States and its allies could not appear everywhere simultaneously, but they could make the Kremlin pay ultimate consequences for almost any type of destruction worldwide, not just nuclear attacks on the United States. This idea was known as the “massive retaliation” strategy: as John Foster Dulles, the Secretary of State during Eisenhower’s era, put it, it meant “the powerful capability to immediately respond with our chosen means and locations.”

In October 1957, when the Soviet Union launched its first artificial satellite, Eisenhower’s approval ratings had been declining for several months. Despite his deep skepticism about the effectiveness of nuclear weapons, he still approved extensive military expansion, allowing for the targeting of more targets.

“You can’t fight this kind of war,” he said at a White House meeting a month after the Soviet Union launched its satellite. “There simply isn’t enough bulldozers to clear the streets of bodies.”

Eisenhower’s successor harbored doubts about nuclear options, even though the U.S. military relied on his investment in it. Moreover, the system became increasingly difficult to manage: with the power of nuclear arsenals increasing, there was an increased likelihood of misunderstandings and miscalculations.

In 1959, the missile era replaced the bomber era, making nuclear decision-making more complex. Intercontinental ballistic missiles orbiting the world at several times the speed of sound were more terrifying than Soviet bombers hovering over the Arctic. Suddenly, the president’s window for major decisions shrunk from hours to minutes, making broader deliberation impossible and highlighting the necessity of having one person hold the nuclear decision-making power.

Around the same time, the Soviet Union surrounded the U.S., French, and British troops stationed in Berlin, creating direct confrontations between the East and West—increasing the possibility of a nuclear war and exacerbating the president’s pressure. If Western countries refused to retreat from any local conflicts elsewhere in the world, the Soviets might invade West Germany, betting that doing so would lead to the collapse of NATO and force Washington to capitulate. Meanwhile, Americans bet that using (or threatening to use) nuclear weapons would deter (or deter) such an invasion.

But if either side crossed the nuclear threshold on the European battlefield, the game quickly boiled down to: Which superpower would be the first to launch a full-scale attack on the enemy’s homeland?

Under this policy of nuclear near-war, every decision by the president could trigger disaster. Staying in Washington meant risking death; leaving the White House could be seen as a signal by the Americans that they were preparing to strike—which, in turn, would provoke fear among the Soviets, prompting them to decide on a preemptive nuclear strike.

In this fervor, the lives and future of civilizations of hundreds of millions of people depend on the cognitive and emotional understanding of the President of the United States and his adversaries in the Kremlin.

The President makes decisions, but the staff are responsible for planning, and their job is to find targets for bombing. By the end of 1960, before Kennedy took over the White House, the U.S. military had developed its first set of plans to coordinate all nuclear forces in the event of a nuclear war. It was called “Total Nuclear War Single Integrated Operation Plan” (SIOP), but it wasn’t really a plan at all.

During the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, U.S. President Kennedy conversed with U.S. Army general Curtis LeMay (second from right) among other senior U.S. military officers.

The “Total Nuclear War Single Integrated Operation Plan” (SIOP) of 1961 envisaged not only directing all American nuclear arsenals against the Soviet Union but also against China, even if China did not engage in a war with the United States. This was more like an order than a real plan. Kennedy’s military advisors straightforwardly (and correctly) told him that even after such a massive strike, there would be parts of the Soviet nuclear arsenal that would survive—and cause terrible damage to North America. This quickly became known as “mutual assured destruction.” According to John Rupert, a defense department official, during a SIOP briefing chaired by General Thomas Powers, a rational voice rose up, “If this isn’t a war against China?” The voice asked. “If it’s just a war against the Soviet Union? Can you change the plan?”

“Well, yes,” General Powers said helplessly, “We can, but I hope no one will think of this because it would completely ruin the whole plan.” “I only hope you don’t have relatives in Albania,” Powers added, because the plan also included bombing a Soviet facility in the small country.

The Commander of the United States Marine Corps, General David Sumner, was one of those who expressed aversion to the plan, stating that it “does not reflect the way America operates.” Luber later wrote that the feeling was like witnessing Nazi officials orchestrating a mass extermination plan.

Since Eisenhower, every president has been shocked by the nuclear options they hold. Even Nixon was astounded by the scale of casualties projected in the latest Situational Operation Plan (SIOP). In 1974, he ordered the Pentagon to develop a “limited” nuclear warfare strategy. When Henry Kissinger requested a plan to prevent Soviet invasion of Iran, the military suggested dropping nearly 200 nuclear bombs at the Soviet-Iranian border. “Are you crazy?” Kissinger exclaimed during a meeting. “Is this a limited option?”

By the end of 1983, Ronald Reagan had heard briefings on the latest SIOP plan and wrote in his memoirs: “Some people in the Pentagon still claim that nuclear war can be won. I think they are insane.” Advisor to Reagan, Paul Nicholls, told an ambassador shortly before his death: “You know, I advised Reagan never to use nuclear weapons. In fact, I told him that even nuclear weapons should not be used, especially in retaliatory strikes.”

At the end of the Cold War, despite the system still being commanded by the president, it had devolved into an almost uncontrollable situation: a highly technological disaster generator aimed at transforming unimaginable options into devastating actions. Each president was constrained: essentially, there was only one command center with virtually no control over operations. In 1991, George H.W. Bush began to scale back this overly complex system, leading to significant reductions in both the number of American nuclear weapons and targets. However, as presidents changed, war planners remained: in the years following Bush’s departure, the U.S. military increased the list of targets by 20%.

Since the end of the Cold War, the United States has undertaken some meaningful reforms, including negotiations on significantly reducing nuclear stockpiles between the United States and Russia, as well as establishing additional safeguards against technological failures. For example, in the 1990s, American ballistic missiles were aimed at international waters to prevent accidental launches. However, if a nuclear crisis erupts, the president would still face plans and options not designed by him or even anticipated by him.

In 2003, the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI) was replaced by the “Strategic Deterrence and Military Deployment Plan” (OPLAN). This plan seemingly granted the president more options than just exterminating humanity, including the option to delay countermeasures rather than immediately retaliate. However, reports indicate that the initial OPLAN also included options to destroy small non-nuclear states. Despite the secrecy surrounding details, military exercises and non-confidential documents over the past 20 years suggest that this modern nuclear plan largely resembles its predecessor from the last century.

The concentration of presidential power, the compression of decision-making time, and the systematic targeting of military planners all work together over more than 80 years to create an institution burdened with significant and unnecessary risks—and the president still retains the right to order nuclear strikes under any reason he deems appropriate. However, there are ways to reduce this risk without compromising the basic strategy of nuclear deterrence.

To limit the president’s reckless actions and lower the likelihood of a world-ending scenario, the first thing the United States can do is commit to the policy of “no first use” of nuclear weapons. Earlier this year, a bill prohibiting preemptive nuclear strikes without congressional approval was reintroduced in the House of Representatives, although it is unlikely to pass. If Congress does not approve, any president could pledge not to use nuclear weapons first through executive orders, which might create breathing space during crises (provided the adversary trusts the president).

Every president should insist that in the face of impending attacks, options available include more limited retaliatory strikes and smaller-scale comprehensive responses. In other words: remove items from “Danny’s Menu” that we do not need, and reduce the existing portions. The United States might only need to deploy a few hundred strategic nuclear warheads—not currently around 1500—to maintain deterrence. Even with such minimal deployment, no country has enough firepower to completely destroy all U.S. secondary nuclear retaliation capabilities through preemptive strikes. If a president orders a reduction in the number of deployed warheads while still maintaining a threat to key targets, it could regain partial control over nuclear systems, much like Congress can limit presidential nuclear options through legislation. This would make the world safer.

Of course, none of these measures can solve the fundamental problem of the nuclear dilemma: human survival depends on an imperfectly functioning system that is always running. Command and control systems rely on technology that must always be operational and minds that must remain calm. Some defense analysts doubt whether artificial intelligence—which reacts faster and more calmly than humans to information—can alleviate some of the burden on nuclear decision-making. This is a very dangerous idea. Artificial intelligence might help quickly organize data and distinguish real attacks from misjudgments, but it is not foolproof. Presidents do not need algorithms for instant decisions.

The officer responsible for safeguarding the “nuclear briefcase” at the president’s side

In terms of preventing large-scale attacks, empowering the president with sole authority seems to be the best choice. In times of urgency, groupthink can be as dangerous as individual madness, and retaliatory orders must be decided by the president—above any bureaucratic institution and distinct from military exercises.

However, the decision to initiate preemptive nuclear strikes should be a political debate. The President should not have the sole right to initiate nuclear war.

But what happens if a president with poor judgment and morals takes office or if the President’s conduct is corrupt during his term? What is the only entity that can directly constrain a reckless President? It is the individuals within the chain of command who must choose to relinquish their duties in order to delay or obstruct commands they deem reprehensible or insane. However, soldiers are trained to obey and execute orders; a coup d’etat is not foolproof. The President can dismiss or replace anyone who hinders this process. American soldiers should never be empowered to prevent commands that contravene reason; manipulating this situation will undermine national security and the very foundation of American democracy itself.

When I asked a former Air Force missile squadron commander about whether senior officers could refuse orders to launch nuclear weapons, he said, “We were told we could refuse illegal and immoral orders.” He paused. “But no one ever explained what ‘immoral’ meant.”

Ultimately, American voters themselves provide a form of security. They decide who will control the top levels of command and control systems. When they go to vote, they naturally consider healthcare, egg prices, and how much it costs to fill up a tank. But they must also remember that they are essentially placing nuclear codes in the hands of someone else. Voters must elect a president capable of clear thinking in crisis and capable of broad strategic planning. They must select leaders with good judgment and strong character.

As the sole steward of America’s nuclear arsenal, the President’s most important duty is to prevent nuclear war. And voters’ most important duty is to elect the right person to bear this responsibility.

(Original article published on the Atlantic Monthly comment website in the United States, with the original title: “The President’s Weapon: Why the Power to Launch Nuclear Weapons Lies in the Hands of an American?” The translation is from the “Dynasty Newspaper” WeChat public account, does not represent the views of Guanchao.com.)