Recently, chatting with a friend who specializes in global asset allocation, he shared with me an interesting shift.

He mentioned that over the past decade, for some international investors, when the global markets were turbulent, investing in the United States was seen as a safe haven.

Behind this, there is a concept that has been validated by the market—”The Exceptionalism of the U.S.” It means that no matter how chaotic the world gets, the U.S. market can quickly absorb shocks and even thrive on its own.

However, this pattern seems to have broken down this year.

He asked me somewhat perplexedly, “Do you think it’s possible that the biggest storm right now might actually come from the safe haven itself?”

After our conversation, I reviewed the latest Global Financial Stability Report by the International Monetary Fund and found some data that increasingly made me feel his confusion might be touching upon some profound changes.

Tan Zhu also wanted to share some observations in this regard.

Observation One: The “Exceptionalism of the U.S.” in the Capital Markets is Disintegrating

A Simple World, a Complex Logic YU YUAN TAN TIAN

In the past, the U.S. market was like a huge magnet. When trade frictions erupted, investors instinctively believed that capital would flee to the most secure place—the U.S. But this year, things have turned around.

This is the situation of global stock market volatility since President Trump took office just one hundred days ago. The U.S. stock market, which had been maintaining its gains, continued to fall repeatedly under the threat of tariffs.

Represented by the S&P 500 index, after Trump took office for the first three months, it fell by more than 14%, significantly lagging behind most of the global markets.

A similar situation occurred in July this year.

At the beginning of July, the U.S. announced tariffs of up to 40% on Japan and South Korea. After the announcement, a strange scene unfolded. Asian and European markets reacted calmly, and even generally rose, with Japanese and Korean stock markets rising by 0.26% and 1.81% respectively on the day.

On the contrary, the U.S. stock market itself fell back.

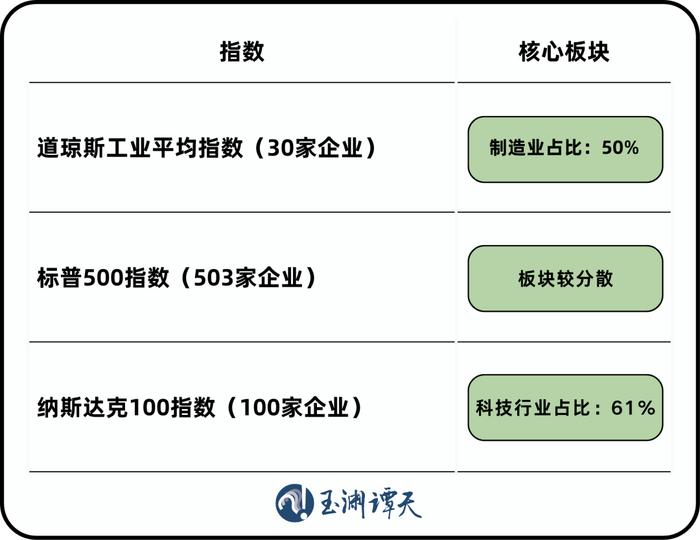

The three major indices all closed lower, with the Dow Jones Industrial Average leading the decline.

This suggests that the market believes that the impact of the US’s tariffs on itself is greater than on others. When a country initiates a trade war against multiple countries, the impact accumulates and ultimately reciprocates back to itself.

Behind this shift lies a trend: the sensitivity of various markets to Trump’s policies is continuously declining, with the domestic market in the US being the most directly affected.

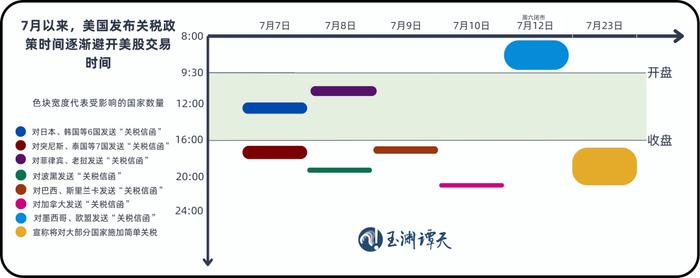

Perhaps it is precisely because the impact of tariff policies on the US is more significant that the US government deliberately avoided trading hours for its tariff policy announcements after the first two days.

On July 23rd local time, the US government launched a new round of tariff threats, announcing that it would impose simple tariffs ranging from 15% to 50% on most other countries around the world. By then, the US stock market had already closed.

Yang Zirong from the Institute of World Economy and Politics at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences shared with Tan Zhi that

The US’s tariffs on various countries have a cumulative effect, posing the greatest impact on the US itself. Moreover, the US’s unpredictable style is accelerating the formation of this market expectation.

Observation Two: The US’s most stable stock index has the highest volatility.

Simple logic reveals complex world YU YUAN TAN TIAN

One reason is that the Dow Jones Industrial Average covers 30 American companies primarily in industrial, consumer, and financial sectors, with manufacturing enterprises making up the largest proportion.

In the context of global trade frictions, the most pressured sectors for U.S. stocks are manufacturing and consumer-facing ones. According to data from Yale University’s budget lab, the current actual average tariff rate in the United States is 16.6%. However, by August 1st, this figure will rise to 20.2%.

Related survey data shows that over 40% of U.S. manufacturing and service industries have reported a decline in profits due to trade barriers, which are gradually becoming evident in corporate financial reports.

Another fact is that although the Dow Jones component stocks are mostly domestically based, their supply chains and markets are highly globalized. The development of these companies cannot be separated from international trade.

However, now, the U.S. government is using tariff policies to “cut off” this connection, making the once “most stable” index unstable.

U.S. stocks are increasingly like a “globalized company + a few tech stocks” conglomerate.

A Simple Logic on a Complicated World – Yu Yuan Tan Tian

Today, the U.S. government is dismantling the globalization system that supported it.

Therefore, many economists have made judgments: Today’s U.S. stock market reflects more than just the economy of the United States; it also reflects the profitability of globalization companies. The current U.S. stock market is increasingly distant from the reality of most American companies, and the damage done to globalization will diverge from the profit logic of U.S. stocks.

Another reason is—the three major indices are clearly dependent on a few tech giants.

The S&P 500 and Nasdaq use “market capitalization weighting,” with the largest weights being those tech giants; while the Dow Jones Industrial Average uses “price-weighted” index, which can boost the overall index when high-priced stocks strengthen.

The S&P 600 small-cap index, which is more sensitive to the domestic economy, has been weakening since the beginning of the year, showing a far weaker overall trend than the broader market.

Similar situations have also occurred with the Russell 2000 Index.

As an important indicator for tracking the performance of small and medium-sized enterprises in the United States, the Russell 2000 Index has gradually pulled away from the broader U.S. stock market. From the new U.S. administration to July 24th, the Russell 2000 Index fell by 2.84%, with a gap of over 7 percentage points between it and the S&P 500 Index.

If the three major U.S. stock indexes cannot fully reflect these indicators that represent the real feelings of the American economy, will international capital still easily make asset allocation decisions based on their rise and fall?

Observation Four: International investors cannot easily rely on the exchange rate of the dollar to make money anymore

Simple logic looks at complex worlds YU YUAN TAN TIAN

The Chairman of the White House Council on Economic Advisers mentioned in the “Hyde Park Agreement” that the current issue for the United States is the high dollar index, which must be addressed to allow the depreciation of the dollar, thereby reducing export product prices and enhancing competitiveness, allowing manufacturing to return to the US, and enabling the US economy to profit from exports.

Whether or not manufacturing will truly return remains to be seen, but this clearly does not bode well for international investors.

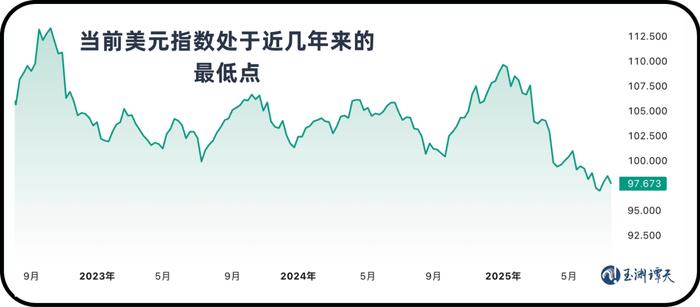

Since the beginning of this year, the dollar index has indeed weakened continuously, reaching a low point not seen in recent years. The three elements supporting its strong position—finance, technology, and stock markets—have also begun to show signs of fatigue.

On one hand, the US’s international asset balance has also reversed. By 2025, the US’s net foreign liabilities will approach 90% of its GDP, setting a new historical high. Its assets invested abroad will no longer generate income.

On the other hand, looking at tech stocks, in the first quarter of 2025, US tech capital expenditures did contribute nearly a point to GDP, but this was the last time such a situation occurred before the peak of the internet bubble in early 2000.

Today, seven stocks have formed a “three-strong, two-equal, two-weak” pattern. As of July 25, the stock prices of Nvidia, Meta, and Microsoft have risen by 20% within the year, while Amazon and Alphabet (parent company of Google) have slightly increased, but Tesla and Apple have fallen by 17% to 12% respectively.

Although the dollar has been strengthening over the past decade, apart from the top ten stocks, the future earnings forecast for the S&P 500 has not grown for three consecutive years.

Thus, we see that international capital is starting to shift quietly. In the second quarter of this year, US long-term bond funds have withdrawn nearly $11 billion, marking the largest outflow since 2020. Just in May alone, European debt exceeding one year attracted a net inflow of €97 billion, the highest monthly level since 2014.

Citibank’s analysis suggests that this is likely a manifestation of investors withdrawing from dollar assets.

In addition to the trending changes in data, an increasing number of investment managers are now publicly stating that due to adjustments in asset allocation frameworks by the US tariff policy, there is a reduction in US assets and an increase in other international assets.

Looking back, several views once believed unquestionably by the market—that dollar assets are the most trustworthy and that the US market is a safe haven for global capital—are now undergoing a reality check.

They are all being eroded by the same force. This force is not from external enemies but from within, a “strategic” one.

When old consensus is broken and new rules have not yet been established, the world enters a period of uncertainty known as a “cognitive gap.”

For us all, it might not be a bad thing. It reminds us to stop using past maps to find our way forward.